Solovay-Strassen Primality Test Series

After deep diving into quadratic residues and Euler’s Criterion and such, now we can finally just write some code.

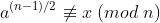

As mentioned in the previous post, there are pseudoprimes that can satisfy Euler’s Criterion. Our way of combatting them is by trying a wide variety of values to check if \(n\) is prime.

Let’s explain the code

Going back to the First Look post, we have this chunk of somewhat code stuff

def is_prime(n, iterations):

for i in range(iterations):

a = random(2, n-1)

x =  if x == 0 or

if x == 0 or  :

return "composite"

return "probably prime"

:

return "composite"

return "probably prime"

Understanding each step

- Pseudoprime control: By running this test numerous times, we can reduce the risk of a pseudoprime sneaking through.

- For each random value

a, we see if

x == 0: isndivisible bya? If yes, thennis compositex % n != y % n: Does Euler’s criterion hold? If not,nis composite- side note: We use

x % nto handle negative Jacobi symbol values by converting them to their positive equivalents.

- side note: We use

Finally, let’s write some code

from random import randint

# I copied this from the jacobi post

def jacobi(q, n):

if n % q == 0:

# base case of when n is a multiple of q

return 0

result = 1

while q > 0:

# extract all the factors of 2 from q

while q % 2 == 0:

q = q // 2

# applying the rule about (2/n)

# we only care about the case of -1, since 1 have no impact on the result

if n % 8 in [3,5]:

result *= -1

# quadratic reciprocity aka flipping the numbers and flipping the sign if needed

if q < n:

q, n = n, q

if q % 4 == 3 and n % 4 == 3:

result *= -1

q = q % n

return result

def is_prime(n, iterations):

for i in range(iterations):

a = randint(2, n-1)

x = jacobi(a, n)

y = pow(a, (n-1)//2, n) # this is that modular exponentiation i mentioned

if x == 0 or x % n != y % n:

return False

return True

And just like that, we understand and have implemented Solovay-Strassen. Try it out. For composite numbers, it’ll generally figure out they’re composite quickly and for prime numbers, it’ll always say they’re prime. Cool, right?

Tradeoffs

As I said at the start of this series, there are trade-offs when it comes to complexity and levels of certainty. Since we had to write multiple blog posts just breaking down the high-level version of the math, I think we can all agree this is complex.

But what about with levels of certainity.

- If it returns False, the number is definitely composite

- If the number is prime, it’ll definitely return True

- If it returns True, the number might be composite (but probably isn’t)

But really, what are the odds the third case will happen?

The worst case odds of a composite number being thought to be prime is \(\frac{1}{2^k}\) where \(k\) is the number of iterations performed. So obviously the more iterations we do, the odds of a false positive drastically decrease. Just 20 iterations puts the odds at 1 in a million.

Even though this is a rather small error rate, this isn’t actually the least error-prone primality testing algorithm out there and hopefully soon, we can deep dive into those too.